Scottish Widows report highlights a yawning gap between what people expect to receive on retirement and the grim reality

Retirement savings have hit a record low, with the number of people putting aside money for a pension falling by 5% last year alone, according to a report this week. Meanwhile, figures prepared for Guardian Money suggest even middle-income workers in company schemes will have to find an extra £600 a month to fund even a basic level of retirement income.

The eighth Scottish Widows annual report on UK pensions found that less than half of the population is putting enough aside for their retirement, with 22% saving nothing at all. Women are in a much worse position than men, with just 42% having adequate savings compared with 49% of men.

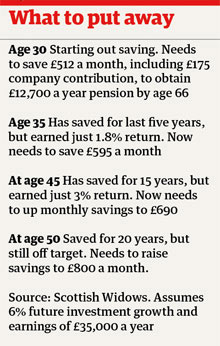

So is there anything you can do? Guardian Money asked a number of pension companies and financial advisers to calculate how much you need to save each month to get a £20,000 income in retirement. We assumed that the state pension will be a flat-rate £140 a week, as proposed by Iain Duncan Smith, which is £7,280 a year. So a £20,000 income would need a private pension of £12,720. But amid falling stock markets, people living longer, and worsening annuity rates, even reaching that figure requires frightening levels of extra saving for decades.

We asked the experts to assume that an individual is earning £35,000 a year, and is in a company scheme where the employer pays in 6% of salary and the individual the same. We chose these figures because 6.2% is the typical payment companies make into stock market-based pension schemes.

According to Scottish Widows, a 30-year-old starting out in the company scheme would have to pay in an additional £162 a month to hit the £12,720 target by 66. In other words, he will have to raise their personal contribution from 6% of salary (£175 a month) to 11.5% (£337 a month).

According to Scottish Widows, a 30-year-old starting out in the company scheme would have to pay in an additional £162 a month to hit the £12,720 target by 66. In other words, he will have to raise their personal contribution from 6% of salary (£175 a month) to 11.5% (£337 a month).

“A £20,000 pension isn’t an unreasonable aspiration for someone earning £35,000, but is likely to require significant sacrifices,” said Ian Naismith, head of pensions development at Scottish Widows.

We also asked what individuals would have to pay if they are older and have been putting 6% of salary (plus the company’s matching contribution) into a scheme since they were 30, if they want to be sure of £20,000 a year at 66.

In recent years, stock market returns have been so poor that the sums built up into individual pension pots have been substantially below expectations. A 35-year-old has been earning just 1.8% on their money over the past five years, while a 40- or 45-year-old has been getting just 3% a year since they were 30. That means people in this position are going to have to increase their payments substantially to make up for the losses and still be on target to hit a decent retirement income.

A 35-year-old will have to increase payments to £420 a month (12.4% of salary), rising to £515 if the person is 45 (17.7% of salary), and £625 at 50 (21.4% of salary). Put another way, a 50-year-old on £35,000 a year who has been saving in a company scheme for 20 years, putting in 6% of salary a month matched by the company’s 6%, will still have to increase their payments to £625 a month and see 27.4% of their salary (21.4% own contribution, 6% from company) to be sure of a private pension of just £12,720 a year at 66.

But it gets grimmer. Scottish Widows’ figures are based on an assumption that investments will grow at around 6% a year. Given that markets have achieved less than half that over the last decade, even finding an extra £600 or so to pump into your pension every month may not be enough.

What if you haven’t started a pension at all? We asked Prudential for figures, assuming the person is a standard rate taxpayer and wants to retire on £20,000 a year at age 66. We allowed for a stock market return of just 3% after charges. On this basis, a 40-year-old will have to put aside £1,493 a month, a 45-year-old £2,008 a month, and a 50-year-old an astonishing £2,856 a month. In other words, if you’re 50 and earn about £35,000 a year, you’ll have to put almost every penny of your earnings into a pension scheme if you haven’t yet saved anything, just to obtain an income of £12,720 a year at 66.

Vincent Smith Hughes, retirement expert at Prudential, says: “Fifty-year-olds who have left it late cannot delay any longer. It’s going to be extraordinarily difficult to save a large pot between now and retirement.”

Tom McPhail, pensions adviser at Hargreaves Lansdown adds: “The great advantage of a pension is that you have tax breaks and very often an employer contribution too; no other method of saving can give you such a generous boost. For longer term investing it absolutely makes sense to invest in equities and for younger investors higher volatility investments in emerging markets equities is just fine.”

But do the figures suggest that saving for retirement through a private pension scheme, invested in the stock market, is throwing good money after bad? Pension schemes work best for higher earners, who can earn 40% tax relief on their contributions. But for a lower earner, picking up just 20% tax relief, and then being forced to buy an annuity at 66, traditional pension schemes may look poor value.

Even some pension sellers admit that an Isa may be a better bet than a pension. “Tax breaks favour higher-rate taxpayers most and someone on £35,000 is unlikely to be in that bracket,” said Naismith. “It might well make sense for them to put the money into an Isa with a plan to move it into a pension later, particularly if they subsequently do pay higher-rate tax. This is especially true of younger people who are tying up the money for longer, but if they save outside a pension, they need to avoid dipping into their savings except in a real emergency.”

For many people in their 30s or 40s, accelerating their mortgage repayment makes more financial sense than paying into a pension. A Guardian Money analysis in April last year found that overpaying a £150,000 mortgage by £250 a month cuts eight years and six months off the 25-year term, and saves the borrower nearly £28,000.

Original Aricle : Guardian Money